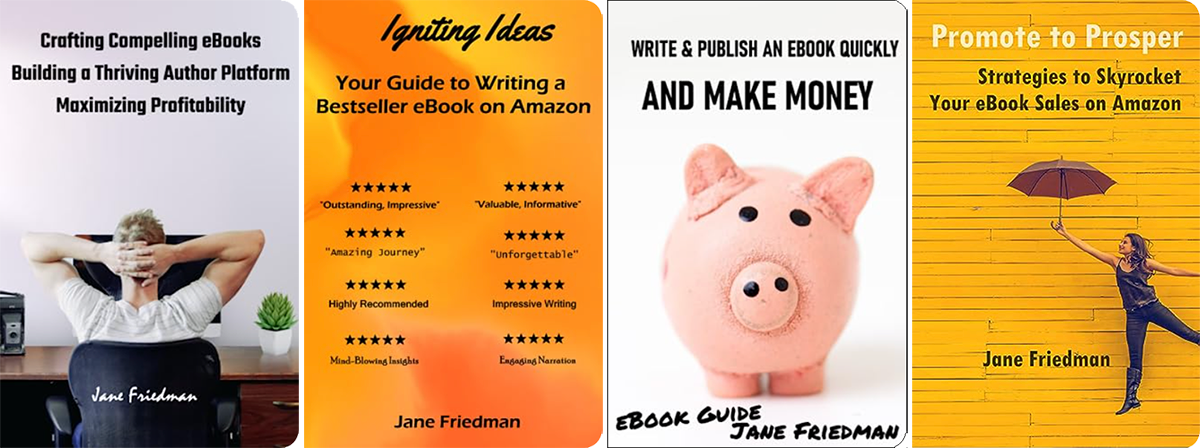

Last week, I sparked some publishing news when I discovered five or six books published on Amazon under my name that I did not write or publish. They were available in print and ebook format, some even with ISBN numbers, published in July and early August 2023. They were automatically listed on my official Goodreads profile without my consent or knowledge. Some of you may have seen my initial post about the matter at my author website.

As of today, the books have been removed from sale, but my initial infringement claim with Amazon went nowhere. While it’s straightforward to report copyright and trademark infringement to Amazon, I could not claim either—the titles in question weren’t pirated or counterfeit editions of existing work, nor do I own a trademark for my name. I tried to file a claim anyway and explained this was a case of false advertising and an abuse of my name, image, and likeness. But as any author who’s dealt with Amazon knows, unless your case fits into a neat box, your cries for help can be ignored. So what do you do if this happens?

If you’re traditionally published, get in touch with your publisher. Their sales and profits are at risk, just like your own. An experienced publisher of any size has likely dealt with these problems before and might be successful in their efforts to get the material taken down. They know what language to use with Amazon and how to escalate the situation as needed. As for myself, I did reach out to my publisher (the University of Chicago Press), but the books were taken down before they had an opportunity to act.

Unfortunately, some authors may not be able to get their publisher to act, or they may simply no longer have a relationship or point of contact. If that’s the case, then the next step is to alert any major writers organizations that you’re a member of. The Authors Guild membership is open to all writers, published or not, although their free legal services are reserved for certain categories of members. Not long after I publicized my problem, The Authors Guild proactively announced it would assist: “We can advocate on your behalf and are reaching out to senior management immediately to let them know that these works are an attempt to trade off your brand and must be removed as infringements of the Lanham Act.”

What is the Lanham Act? In the US, it’s a federal law that legislates the use of trademark. While I don’t have any registered trademarks, anyone who attempts to pass off their own work as someone else’s may be guilty of unfair competition, barred by the Lanham Act. Authors don’t need a registered trademark in order to bring an unfair competition claim. Unfair competition covers likelihood of confusion in the market and false advertising.

Note: For those in the UK/Ireland, see this helpful post for more information about what laws protect you. Also, a UK law firm has written an insightful analysis about moral rights in the UK.

What about right of publicity? It varies by state. Here’s a tool to help you check laws in your state.

Regardless of how you publish, if you find work attributed to you that you did not write, then you can use the violation of the Lanham Act in the US to help make your case. But if Amazon (or whomever) doesn’t agree with you, it may require hiring lawyers to make progress, and most authors I know lack the resources, time, and energy to bring a court case. Which raises the question: Should you obtain a trademark for more immediate remedy?

Whether it’s worthwhile to register for a trademark will vary from author to author. Registering for copyright is easy and cheap and doesn’t require a lawyer. Not so for trademark: You’re probably looking at an investment in the low four figures. The process is also slow, taking a year or more. In some cases, your attempt to register might not even succeed, and you’ll still be out the money.

Publishing lawyer Lloyd Jassin on Twitter/X responded to my situation with the following: “Trademark registration of an author’s name opens doors to Amazon’s Brand Registry, empowering them with takedown tools. The one hitch is the name must be perceived as a mark for literary services. In the post-copyright world, trademark is the new copyright.” (Is it really? That’s another article.) He continued, “The Brand Registry is a quick and cost effective alternative to litigating unfair competition and right of publicity claims. But the mark must be registered, which requires showing consumers perceive the name to be a badge for literary services.”

Even if you don’t use Amazon’s Brand Registry, with a trademark registration number you have something tangible to show Amazon if and when you go through the normal infringement claim process. That said, when I reached out to Ian Lamont, an author and publisher who uses Amazon’s Brand Registry, he said it’s an imperfect system. “Some [claims] are accepted, but others are rejected even though it’s pretty clear the person was violating my trademark (copyright violations are a different story—most are accepted),” he wrote me. “The other thing that really bothers me is Amazon will notify the offending party, who will reach out to me to try to get me to change my mind, but Amazon does nothing to reveal to me the person’s true name or legal address, which are required for any further legal action, such as a cease-and-desist. It’s typically someone using an anonymous Gmail address.”

Self-published authors might have to find creative ways of getting through to Amazon. ALLi’s John Doppler advised me, “First-tier support at Amazon has been worse than useless. However, I’ve had luck getting imposters removed by invoking the magic words misleading customer experience, and if that fails, making a persistent and explicit request to escalate the case to Tier 2 support. Sometimes the second step isn’t necessary if you can make a strong case that this is attempted impersonation and not simply two authors with the same name. But it’s a mess on Amazon right now. They’re floundering in the tsunami of AI garbage. As overworked and overwhelmed as they are, any interaction with support is going to be even more of a roll of the dice than usual.”

Here I must offer kudos to ALLi, who saw this problem surfacing weeks ago and attempted to warn authors. Doppler posted on July 24 to their Facebook group: “We’re seeing an uptick in fraudulent author impersonations on Amazon, but with a new twist. In the past, scammers pirated authors’ books or created terrible knock-offs, then uploaded them to KDP. Amazon’s algorithms would sometimes add those to the Author Central page of the legitimate author.

“That was pretty rare. Now, however, we’re seeing scammers uploading AI-generated garbage with legitimate authors’ names attached to it. Because AI allows them to churn out dozens of these impersonations, the volume of those scams has increased dramatically, and the frequency of incorrect author linking has increased with it. Amazon is reportedly working on a fix to prevent these from being linked to an author without authorization, but until that’s ready, it’s a good idea to check your author page periodically to ensure nothing was added to it without your approval. Regardless of Amazon’s fix, it’s a good idea to search for your pen name(s) and titles once in a while to check for impersonations or piracy.”

While I find Amazon’s systems completely inadequate to meet the current moment, I can understand their initial lack of response—a little bit. Writers report all manner of problems that just don’t meet the bar for removal or infringement. As I spoke out about my issue, countless writers complained to me about books they couldn’t get removed, review bombing, and incorrect metadata. Some complaints may have been legitimate, but the majority were the usual annoyances that writers deal with, not necessarily illegal activity. Regardless, Amazon’s systems need better clarity and more heft for all types of situations, with clear guidance for authors on remedies available to them.

Deciding that you won’t deal with Amazon at all is not a solution to the problem. Outside the publishing community, some people assume I somehow brought this fraud on myself by self-publishing and having an Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing account that was hacked or misused. This was not theft of my KDP account. It was someone using their own Amazon KDP account and uploading several books—even a three-book series!—and passing off those books as authored by me. People can add whatever author name they like to their books. It doesn’t have to match the account owner or tax information. What happened to me could happen to anybody.

Others believe they can save themselves by keeping their books off Amazon (hard to do, if not impossible) or by not publishing in the first place (a strange and self-defeating solution if you want to be an author).

While you can advise your existing fans or community to buy direct or from their local store or wherever you think best, that doesn’t stop the average consumer from pulling up Amazon as their favorite search engine and seeing if you have anything available for sale. That’s what happened to me. Someone was curious about what books I’d published, went to Amazon first, and found these frauds. Thank goodness she had the critical thinking skills to see them for what they were and report them to me. I’ve also been told I should add notices to my bio, website, author profiles, etc., telling people to beware of fakes published in my name. This does nothing to help people who are in the early stages of discovering my work, and it’s not much better than screaming at the clouds.

Anyone who has a name that people search for—whether you publish books or not—is at risk of being spoofed on Amazon. And if you have a lot of work available out in public (websites, newsletters, interviews, show transcripts, etc), people can easily create works and models that mimic you, like this Esther Perel bot.

Bottom line: This problem can be remedied by Amazon if it cared enough to do so. Sebastian Posth, an innovator in book publishing, commented, “The problem is super easy to fix. It is ignored intentionally. However, I do not understand the motivation.” Cynical types say the motivation is more profits for Amazon.

A writer who was observing the unfolding drama wrote at length about the situation, theorizing that Amazon might eventually attract a class-action lawsuit. (Indeed, I have been contacted already by two law firms specializing in class action.) He says, “If sites like Amazon publicly claim that AI allows them to tailor product offerings to consumers while privately telling authors there is nothing that can be done to prevent brand jacking, pirating, fake titles and related frauds—which in turn damage the reputations of authors and publishers—then that disconnect is going to be a centerpiece of future legal action.”

As a final postscript, I realize that many authors—self-publishing authors in particular—have been dealing with these problems already, but I’m the one who got all the media attention for it. Why? Well, my platform and reach helps attract attention, and right now the convergence of generative AI and fraudulent schemes is like chum in the water for journalists. Maybe the media saw in me a figure like them, and clear fraud that might soon affect them personally.